Tengchong, Yunnan Province, China; December 7, 2017

Where he was born? Cleveland, maybe. Or Chicago. Maybe even Pittsburgh. A Polish boy. Catholic, no doubt.

Was he called Joey? Or Little Joe? Or was he the big brother? Did his mom insist everyone call him Joseph, so he would always be respected? Was he the oldest son in the household of a widow, raising his siblings until he went to war? Or was he the delinquent kid his family hoped would straighten out once he joined the army? Or was he, like thousands of others, just a quiet young man who answered his country’s call because it was the right thing to do?

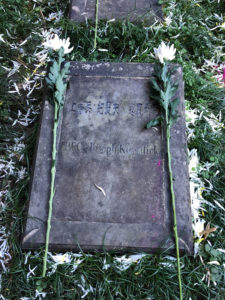

Who could tell? Nothing on the stone in front of me gave those answers.

What I do know is this. After the ceremonies of gift-giving at the War Museum in Tengchong, after the group photos and the tour, after we had come to some appreciation of all that had taken place here in the worst days of 1945, we were led to the National Martyrs Cemetery, to a quiet little square paved with flagstones, surrounded by a grove of bamboo, and 19 gravestones laid flat in the earth, with the names of the Americans who died in the final assault to take back this strategic town.

What I do know is this. After the ceremonies of gift-giving at the War Museum in Tengchong, after the group photos and the tour, after we had come to some appreciation of all that had taken place here in the worst days of 1945, we were led to the National Martyrs Cemetery, to a quiet little square paved with flagstones, surrounded by a grove of bamboo, and 19 gravestones laid flat in the earth, with the names of the Americans who died in the final assault to take back this strategic town.

Each of our party was given a chrysanthemum and told where to stand. Then we were asked to place the flower on the grave in front of us, to honor them the way the Chinese honor their fallen sons.

And Joseph Kowalick, Private First Class, United States Army, was my son.

Were he alive, he would be by now an old man and full of years, aged 93 or thereabouts, perhaps with children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren. It is hard to imagine a life cut down so young, harder still to think he had almost made it to the end. A few more months and the war would be over. Hard to die here, so far from home, yet so near to the rest of his life.

And the Chinese knew that, even in those days of chaos and violence. By the end of the battle, there was not a single building in Tengchong that was undamaged by artillery or small arms fire. Over 100,000 Chinese troops and civilians died in the last months of fighting in western Yunnan. Close to 1,500 American pilots and crew members died flying the “Hump” to support and supply them. And thousands of other Americans gave their lives in the final days of the Chinese campaign.

But these 19 were special. They died for this town. And even as the Chinese were burying their own dead, they wanted to give these boys their due.

The bodies had been given to their American commanders. Some were buried in U.S. military cemeteries abroad. Others were repatriated and now lie in hometown graves in places like Kansas and Vermont and Mississippi.

But the Chinese asked for the soldier’s clothing, the bloodied combat uniforms worn when they were killed. And these, they buried in the same way they buried their own sons, the blood forever mixing with the soil for which they died — a special honor, in this quiet grove of bamboo.

I laid the flower on Private Kowalick’s grave. And then all of us solemnly bowed three times. It is the way Chinese people honor their ancestral tombs. It is their way of saying, “Joe, you’re family now. Now and always.”

I laid the flower on Private Kowalick’s grave. And then all of us solemnly bowed three times. It is the way Chinese people honor their ancestral tombs. It is their way of saying, “Joe, you’re family now. Now and always.”

And maybe this further explains the welcome we have received, the kindness we have been met with from the moment we landed. I have had this strange sense that I have been adopted, without fully knowing why, until going outside this quiet enclosure and venturing through the Martyrs’ Cemetery, up a narrow staircase on a steep hill towards the shrine.

On either side, as far as can be seen, are the gravestones of more than 3,200 Chinese troops killed in the last days of the Western Campaign. They represent a small fraction of those who died. They are buried among the trees, in the beautiful forest, much like the landscape they last saw.

Inscribed on each stone is a name. I ask Colonel Ma, “Are there many unknowns?”

He is serious. “No,” he says, “they are all accounted for. We know the name of each and every one.” He thinks a moment. “Of course,” he says, “we cannot be certain that the bones and ash buried under each stone actually belong to the name inscribed above them. There may be remains of two or three soldiers in one plot.”

He pauses. Then he continues solemnly, “What does it matter? They are all together now.”

And that is the moment when I know I have not been walking here alone, that I am in the company of Nicodemus who was on my mind as I made my way here, that I am touching the wounds and holding the shroud of the Crucified — Americans and Chinese and, yes, Japanese — those buried here and those who sleep for a time in unmarked graves in the impenetrable forests around us. I know that if we were more able to grasp in life the truth that we are all together now, there would be less need to grasp it in death.

And that is the moment when I know I have not been walking here alone, that I am in the company of Nicodemus who was on my mind as I made my way here, that I am touching the wounds and holding the shroud of the Crucified — Americans and Chinese and, yes, Japanese — those buried here and those who sleep for a time in unmarked graves in the impenetrable forests around us. I know that if we were more able to grasp in life the truth that we are all together now, there would be less need to grasp it in death.

And I wonder if it is that lesson the Lord is hoping we will take to heart before He returns, as He patiently listens to the squabbling of the living, and the breathing of the dead, their blood at rest in their shrouds here in this garden, waiting for the stones to be lifted and life to begin at last.