Somewhere over the North Pole, on the way to Shanghai, 12/4 – 12/5/2017

D uring World War II, my father was a young brigadier general in the Army Air Corps, serving in the Pacific theater. He flew bombers over “The Hump,” a particularly treacherous section of the Himalayas, and helped organize the composite wings of the Fourteenth Air Force, merging teams of Chinese and American airmen into a single unit against the Japanese over a front that stretched more than 700 miles. In Ceylon (present day Sri Lanka), he met my mother, a young Army major assigned to the staff of the Supreme Allied Commander for Southeast Asia, Lord Louis Mountbatten. My parents married in 1946 in Nanjing and continued to serve in China for two more years.

uring World War II, my father was a young brigadier general in the Army Air Corps, serving in the Pacific theater. He flew bombers over “The Hump,” a particularly treacherous section of the Himalayas, and helped organize the composite wings of the Fourteenth Air Force, merging teams of Chinese and American airmen into a single unit against the Japanese over a front that stretched more than 700 miles. In Ceylon (present day Sri Lanka), he met my mother, a young Army major assigned to the staff of the Supreme Allied Commander for Southeast Asia, Lord Louis Mountbatten. My parents married in 1946 in Nanjing and continued to serve in China for two more years.

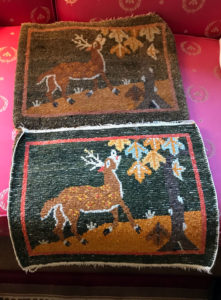

I n our home, we have several pieces of art and furniture from China, part of my parents’ legacy. One of these is a small saddle blanket from Mongolia, a gift to my dad from Mao Tse-tung.

n our home, we have several pieces of art and furniture from China, part of my parents’ legacy. One of these is a small saddle blanket from Mongolia, a gift to my dad from Mao Tse-tung.

In September of 1945, a month after the Japanese surrender, American diplomats organized a conference between the Chinese Communists under Mao and the Kuomintang, or Nationalists, under General Chiang Kai-shek. Mao, considered a rebel and criminal by the Nationalists, was granted safe conduct under American protection to and from the conference in Chongqing. My father was the pilot who flew him from his base in Yunnan province. At the end of the return journey, Mao presented my dad with this blanket as a token of his thanks.

In October, my older brother Bruce, who spends a fair amount of time in China on business, called me up and informed me that the World War II museum in Tengchong was planning to honor our father on the anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Of course, we both would need to be there, so I made plans to spend 72 hours in China. And, of course, we needed to bring a present of some kind. What better gift than Mao’s blanket? It’s in my suitcase, in the compartment above my seat, as I write this.

I confess I am a little ambivalent about giving it up. I have seen this blanket nearly every day since my childhood, with its twin portraits of a reindeer stretching its neck upward to reach a leaf hanging from a tree. When I was very young, it hung over the back of the little rocking chair in the den, from which I used to watch cartoons nearly every Saturday morning. It is a piece of my father – really of both my parents. They have passed on, so letting go of this now stabs me a bit. But the blanket is also a piece of history, and a part of the Chinese people. If I kept it, I’m afraid that over the next few generations the story behind it would be forgotten. I don’t want to see it go for five bucks should a future great-grandchild offer it at a garage sale. And it needs to be taken care of – cleaned up and restored a bit – so making it a gift to the museum seems the perfect thing.

Once we let this gift be known to the Chinese, the blanket turned out to be more cause for excitement than the party for my dad. I mean, sure, Pa was a war hero, but we are bringing back a relic of Chairman Mao! There is talk of an interview with the China Daily, the official newspaper of the Communist Party, and there will be more than one banquet, I suspect.

Two other things about this trip.

First, its crazy route: Pittsburgh to Minneapolis to Toronto to Shanghai. That gets me only into China. Then add another 3,000 kilometer trek west to Kunming and a final flight to Tenchong on the border with Myanmar. And back again. In six days. It is an odyssey, as if filmed in fast-forward.

First, its crazy route: Pittsburgh to Minneapolis to Toronto to Shanghai. That gets me only into China. Then add another 3,000 kilometer trek west to Kunming and a final flight to Tenchong on the border with Myanmar. And back again. In six days. It is an odyssey, as if filmed in fast-forward.

Second, I am going not only as my father’s son, but also as a bishop of the Church. It turns out our hosts are very interested in this piece of who I am, and on Friday (December 8) I will have meetings with government officials and members of the China Christian Council in Shanghai.

All this makes it a pilgrimage, a sacred journey of huge import for my soul. Beginning with Nestorius, through the period of Mateo Ricci and the great Catholic missionaries, into the work of the China Inland Mission and the Anglican presence in Shanghai and elsewhere, those Christians who ventured to China must have felt as if they were fulfilling the command at the end of Matthew’s Gospel – to be Christ’s witnesses to the ends of the earth.

Over the centuries, there have been thousands of saints and thousands of martyrs in China. Since 1979, the Church has gradually been allowed to re-assert its life in the Gospel, under careful government oversight. And now, in a turbulent and dangerous world, perhaps the Christian mission to be ambassadors for Christ and ministers of reconciliation (2 Corinthians 5) may be more urgently needed than ever. Perhaps God will use this visit as a small but important addition to that work, a single stone in a bridge of His own making.

So, yes, I go to remember and honor my father – an act of filial piety the Chinese may particularly appreciate. I go to spend a little time with my brother, whom I love very much and don’t get to see often enough. I go to meet Christ, who is waiting for me in those who welcome me. And I go to learn from my sisters and brothers at the ends of the earth, to learn more about what our mission might look like in Pittsburgh, as God leads us on the road to love, teach and heal in the Name and power of Jesus.