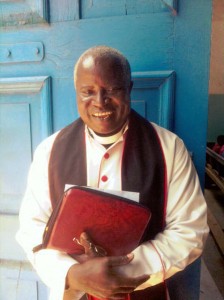

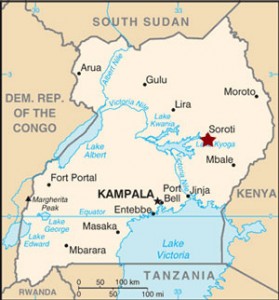

The Right Reverend George Erwau, my Lord Bishop of Soroti, is a cheerful, ebullient man, built like a rugby player, with a strong evangelical faith and an active and creative mind. He presides over a diocese of 70 clergy serving 48 parishes, which comprise a baptized membership of roughly 700,000 Anglican Christians. Yes, you read that right. Each parish may be divided into four or more congregations, each in turn, under the immediate care of a lay reader. On Sundays, the priests get around from service to service on a bicycle. You know you’re a cardinal rector when somebody gives you a motorbike. At ordinations, each of the priests is solemnly presented with a new set of tires.

The Right Reverend George Erwau, my Lord Bishop of Soroti, is a cheerful, ebullient man, built like a rugby player, with a strong evangelical faith and an active and creative mind. He presides over a diocese of 70 clergy serving 48 parishes, which comprise a baptized membership of roughly 700,000 Anglican Christians. Yes, you read that right. Each parish may be divided into four or more congregations, each in turn, under the immediate care of a lay reader. On Sundays, the priests get around from service to service on a bicycle. You know you’re a cardinal rector when somebody gives you a motorbike. At ordinations, each of the priests is solemnly presented with a new set of tires.

The work of the clergy is arduous. There is always the problem of funding. Clergy salaries are scandalously low, and they tend to have large families, like nearly everyone else in rural Uganda. Paying school fees for their kids (which everyone must do, even in government schools) and putting food on the table take every shilling. If a child gets sick with malaria, it can cause a financial crisis. Of course the clergy know how to grow their own food, like all Iteso, and this rainy season is very fruitful, but the time they spend in their gardens takes time away from the priestly tasks of pastoral care, teaching and evangelism. When you are the only priest for nearly 10,000 people, that does add some stress to your life.

In spite of all the challenges, I have seen few people as spiritually alive as these dear friends. They seem to trust God for everything, and will tell you so with laughter, because they have no choice, and because they have seen Him provide again and again. They all went through the wars; they all lost loved ones during the LRA insurgency. They have seen homes burned (in some cases their own), children abducted, their villages mined, their wells salted. They have lost 90 percent of their cattle, the traditional wealth of the Iteso. Because of the way people behave under the pressure of war, the conflicts of the last 30 years have left major fault lines between families, among parishes, among the clergy themselves. Over the last four years, God has slowly been healing them, a process which began with a clergy conference for the diocese. I was present then, and it was one of the most remarkable beginnings of reconciliation I have ever witnessed. In the Diocese of Pittsburgh, we might take heart that God can easily handle anything we can dish out to Him or to each other. Compared to the bloodshed, betrayals and abandonments that this war produced, schism must take a back seat.

The diocese is now moving forward under Bishop George’s leadership, and the vision he is offering them is bold. It also dovetails remarkably with Pilgrim’s own mission. For the last five years, even before he was consecrated, I have been working with the bishop carefully toward a partnership between the two entities. Every time I arrive, he and his wife, affectionately called Toto Florence (“toto” is Ateso for “mom,” a universal term of respect for the mothers of the Church here), greet Betsy and me like the family members we have become. This visit is perhaps even warmer.

At the bishop’s invitation, I preach two services at the cathedral. The 6:30 a.m. service, in Ateso and English, is attended by about 2,000 people. When I arrive at 6:15, the light is just filtering into the cathedral, but the place is already nearly full. I greet several friends in the sacristy, am ushered into the side entrance and directed to sit in the seat next to the bishop’s chair. I kneel in prayer as the choir begins and the first thing I give thanks for is the power failure. The terrible euro-techno electronic keyboards one runs into everywhere in African churches, and their companions from hell, the amplifiers, have been totally silenced, and the people are reduced to singing the way they did 30 years ago. The Iteso sing like the Welsh — robust and open, but their harmonies are closer to Russian Orthodox polyphony; many of their hymns have the evangelical fervor of the missionaries, but are native creations, rich in their own metaphors. They keep time by hand-clapping which, by the third verse, creates a wave of subtle syncopations breaking out here and there across the crowd. Eyes closed, I drink it in, and am interrupted only by George’s hand on my shoulder.

After greeting me, and informing me that my team and I are having dinner at his house on Monday , he joins the opening of the liturgy, led by the sub-dean and vicar, and after the reading of the Epistle, says, “OK, let’s go.” Then he takes my hand and walks me to the front of the chancel. He introduces me as “President of Pilgrim, Bishop of the Diocese of Pittsburgh in the Episcopal Church, a son of Teso, a friend of Soroti, my dear friend and brother bishop.” He concludes, “My brother, you are most welcome,” and gives me a bear hug to huge applause. After the Gospel, by means of a miraculously restored sound system, I preach. And after my sermon, I leave to preach to the kids at Beacon of Hope, whose service begins at 8 a.m. Following breakfast at home, I head back to the cathedral for the 11 a.m. English service and there preach a third time. Compared to some Sundays I have had in Soroti, this is a light schedule.

The next morning, William, Angella and I accompany George to his home village of Achetgwen. As we pound over the ruts of a goat track in his Land Cruiser, he roars, “The name in Ateso means Chicken Droppings! Ha! Ha! Ha!” It reminds me of hamlets in my father’s home area of northern Arkansas, with names like Pig Snout and Frog Hollow. But the vision God has given George is considerably bigger than the name.

We get out at the primary school the government has built in partnership with the Church of Uganda on land the bishop has donated from his family’s holdings. There are nearly 600 kids here. We meet the teachers and school head, sign the ubiquitous guest book, and hear how it all happened, from nothing to something, mainly by prayer.

Then George moves us briskly to the adjoining areas where he has already built a church. “We laid the foundation, got the posts up and ran out of money. So we just got down on our knees and prayed. Every day. And after two months a Korean man who had got lost drove past the church and asked what was happening. When we told him, though he was not an Anglican, he was so moved, he gave us thirty million (about $12,000). The church was finished in another two months, like it had dropped down from the sky. Now, we need accommodation for the lay readers and a health clinic.”

The health clinic is why Pilgrim is here. After five years of explaining ourselves, it feels to me as though the Bishop of Soroti has taken an inspired leap and now totally gets it. He gets holistic development. He sees how the kids studying a half-mile away can’t learn if they’re sick. He sees they need something beyond graduation and is hoping we can help him develop a vocational training center (something we have been dreaming about for years) next to the school. He sees the necessity for food security, describes a vision for mechanical crop processing units at the center of farmers’ co-operatives, and when I remind him I have been talking to him about such MFPs (see earlier post) for five years, he says, “That’s a very good idea!” And we both laugh. By the end of the morning, we have prayed over the whole project and made copious mental notes as to how to go from here. All we lack is money and manpower, but God will provide.

The evening brings a wonderful dinner at the bishop’s house, hosted by Toto Florence: a superb potluck of chicken, goat, chapati, curried vegetables, tilapia, and tea. There, many old and new friends, most notably Sarah, the head of the Mothers’ Union, a woman with enough talent and energy to run General Motors and a key player in our going forward, since the MU is a major organizing force in the life of Iteso communities. Many speeches conclude the evening, with time for prayer, and when I am asked to bless the whole company, I do.