[Click the images below for larger versions]

[Click the images below for larger versions]

If you have read this blog from my previous trips to Africa, you already know some of the basic facts about malaria in Uganda— that this country has the highest transmission rate in Africa, that Teso leads the nation in new malaria cases, that this scourge takes more lives than HIV/Aids, TB, or any other disease. You also may know that Pilgrim introduced an innovative protocol in 2009 that effectively stopped malaria for 177,000 people in the district of Katakwi. For a long time people found it hard to believe that a small, upstart organization like ours could achieve such results, but after years of patient effort, Pilgrim earned the ear and the respect of several major donors, including the President’s Malaria Initiative and the Global Fund, culminating in a 2.5 million dollar grant over the next four years from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The 2009 protocol, as extensive as it was, did not collect enough reliable information to prove that our strategy of co-ordinated spraying of houses and treatment of all children under the age of fifteen, was the reason for the rates of reduction. This grant will fund a much more rigorous pilot study which will involve about 38,000 people in Katakwi and hopefully provide data of international significance.

If you want something big done in Uganda, especially in the rural areas that hold over 80% of the population, you need the help of the churches.

It is a comparatively new idea for the Church to invest itself in addressing the problems of this life. In the past, preachers have focused on salvation for the life to come, and not focused on the causes of poverty and disease. Over the last several years, however, this has been slowly changing. Pastors are being better trained, and there is a growing awareness that the Bible clearly proclaims God’s care for the welfare of all His children in the time of this mortal existence. And, particularly over the last decade, the churches have begun to come together across theological and denominational lines to develop a common basis for addressing human ills. In Teso, this has largely happened through the influence and leadership of Pilgrim.

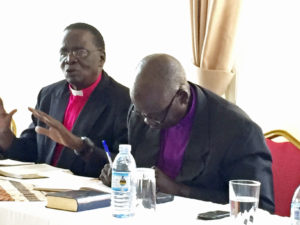

Dr. Dorothy Echodu talking with Bishop Eitu and CMP coordinators the Reverend Sam Eibu and Helen Atilia

The Church Malaria Program (CMP) is the brainchild of the Reverend Sam Eibu. Sam is actually a Baptist, but he trained at Eastern Mennonite University in Virginia. CMP began three years ago as an idea, supported by very few people. The leadership, however, has been persistent, and over time pastors and bishops have come on board one at a time; a small grant from my discretionary fund has allowed them to begin planning an education and prevention effort to be rolled out in all the churches of Teso, in conjunction with Pilgrim’s Katakwi initiative. On Tuesday morning our CEO Dr. Dorothy Echodu, Doris Otim our new Executive Director for Uganda, other senior Pilgrim staff and I meet with the core group of leadership to hear from them, encourage them, and help them shape their plans.

The bishops have turned out in force, which is very good to see, and one or two who could not be here, including the local Anglican bishop, have sent representatives. (The Catholic Church is missing from the table, which is no surprise. Co-operation with Protestants is still a complicated subject. I make a mental note to connect with them through other channels). As always, the meeting agenda is read by the chair, there are prayers and introductions, followed by a period of “testimonies” by the bishops.

One by one, they recount their experience with malaria in their parishes. They are tired of all the funerals: sometimes you will be going out to bury someone and on your way another is at your door. They talk about the ineffectiveness of the approach from the Ministry of Health— to come, talk, leave pamphlets with lots of information, then go away. Everything in Uganda is about relationships, and many of those are rooted in the Church, so as accurate and well-meaning as the information may be, it falls on deaf ears. Then there is the general hopelessness of the people— a belief that the problem is intractable. If it has been with you always, why think it can be changed now? Furthermore, people often delay in seeking treatment, afraid of the expense, telling themselves they will get better on their own in a couple of days, or self-medicating with leftover drugs— this can be particularly dangerous since some of the symptoms of malaria are the same as with typhoid or diabetes. Finally, there are pastoral and theological issues. Pastors generally rely on prayer and laying on of hands, binding the disease in the name of Jesus, then telling the person not to seek treatment so that the cure may clearly be to the glory of God. There is also a widespread belief in positive confession— if you believe you are already cured, then you will be! Clearly there is some work to do.

Dr. Echodu and the Pilgrim team address the two areas in which we believe the churches can be most helpful at this point: vector control and education. The elimination of mosquito breeding sites is one of the simplest and most effective ways of reducing malaria transmission. Getting rid of vegetation near dwellings, filling in pools of standing water, covering water tanks and pit latrines, setting up simple mosquito traps in and around the house— an inverted plastic bottle in a cup with a bit of honey at the bottom, much like a yellow-jacket trap in the US, is a great instrument— all of these can make a huge difference. Education, particularly countering myths about malaria and emphasizing early treatment, can come from the pulpit in a five-minute message every Sunday, while local church committees which take advantage of existing structures— like the Mothers’ Union— can spread the word and help in compliance.

For my part, I emphasize my hope that the churches will not just be seen as an extension of the Ministry of Health, but that we might do this in a way that clearly lifts up Jesus Christ and glorifies God by giving Christ’s dignity and power to His people. engage the bishops in a conversation about the Biblical basis for taking care of our mortal bodies, that we are made in the image of God, that our bodies are the Temple of the Holy Spirit and the seed of the future Resurrection. I point out that Jesus addresses a similar hopelessness in John 9 when he is presented with the man born blind (Rabbi, who sinned: this man or his parents?) and rejects it categorically. As for positive confession, it is no different than the man in the letter of James who says to a hungry and naked person Be warm, be filled! without actually doing anything to relieve their necessity. We come up with a plan to develop a Sunday-by-Sunday Biblical approach to malaria— 54 texts, each followed by a short expository paragraph and a prayer, all in Ateso— that can be used across the congregations represented in the CMP, to be followed up with pastoral training and gathering of feedback. Plans for a public “launch” are laid, and Dr. Echodu volunteers the kids at Beacon of Hope to help with that event.

The meeting ends with prayers and lunch. There is an atmosphere of enthusiasm and determination, and two or three concrete next steps, with a secretary appointed to follow up. Sometimes in Africa, as in the US, when I leave a meeting, I am not sure anything substantial has come out of it. This time, it feels as though, by the grace and power of God, something life-changing could be about to happen.