Since 2007, I have helped direct Pilgrim Africa, an ecumenical ministry of evangelism and redevelopment for northeast Uganda. I will be writing and supplying updates over the course of my current trip to that region to support the work of Pilgrim Africa in public health, malaria control, education, and agriculture; to build relationships for the Episcopal Diocese of Pittsburgh with the churches of Uganda; and to explore mission possibilities for us as a diocese, especially in the areas of medicine and education.

Since 2007, I have helped direct Pilgrim Africa, an ecumenical ministry of evangelism and redevelopment for northeast Uganda. I will be writing and supplying updates over the course of my current trip to that region to support the work of Pilgrim Africa in public health, malaria control, education, and agriculture; to build relationships for the Episcopal Diocese of Pittsburgh with the churches of Uganda; and to explore mission possibilities for us as a diocese, especially in the areas of medicine and education.

February 8, 2018 Day 1

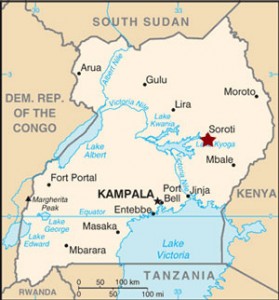

The trek to Soroti is a pilgrimage. Flights from Toronto to Kampala via Istanbul and Kigali, then a journey by road of 360 kilometers to this small town which is the headquarters for Pilgrim Africa’s rural operations. Monday and Tuesday were days of travel, and today begins the agenda for the trip.

I am traveling with Betsy and with the Reverend Dr. Dan Hall, surgeon and priest of the Diocese of Pittsburgh. Over the next five days we have the following tasks:

- Visit Saint Andrew’s School in Buwologoma. Thanks to Ann McStay of St. Paul’s, Mt. Lebanon, and with the sponsorship of the Episcopal Diocese of Pittsburgh, the United Thank Offering made a grant of $76,000 for new construction in this institution which serves blind and hearing-impaired children. My visit is to ensure the funds were spent as required and to nurture the relationships begun through the grant.

- Visit Beacon of Hope School, Pilgrim Africa’s boarding school in Soroti. Begun in 2006 as a sanctuary for former child soldiers and girls trafficked during the insurgency, BOH has evolved into one of northern Uganda’s premier secondary schools, featuring (among other things) a robotics program that is drawing international attention.

- Visit the Soroti branch of the Bible Society to arrange for the purchase of Bibles for churches in the Soroti and Katakwi districts, an ecumenical outreach that will benefit both Protestant and Catholic parishes.

- Attend a clan gathering among old friends in Usuk where Betsy and I are expected as guests of honor, and where I will participate in an outdoor Mass for several hundred people.

- Visit field operations of Pilgrim Africa’s anti-malaria protocol in Katakwi. This study, funded by the Gates Foundation, will likely eliminate malaria for the majority of 38,000 people and lay the groundwork for greatly expanded work.

- Participate in a joint retreat and meeting for Pilgrim’s Ugandan and American boards, with particular attention to strategic planning for the future.

The day begins with a visit to the Beacon of Hope, and travel will branch out from there. Please keep us in your prayers!

The camp is gone now, and the people have almost all been resettled into traditional lands. Since then, Pilgrim has concentrated on the task of helping them become food-secure. There have been floods and drought and crippling financial pressures that made us pull staff from the fields. Somehow, by the grace of God, we have managed to keep going, and the original vision is at last slowly becoming a reality.

The camp is gone now, and the people have almost all been resettled into traditional lands. Since then, Pilgrim has concentrated on the task of helping them become food-secure. There have been floods and drought and crippling financial pressures that made us pull staff from the fields. Somehow, by the grace of God, we have managed to keep going, and the original vision is at last slowly becoming a reality.  Wherever you travel in Uganda, you will meet schoolchildren.

Wherever you travel in Uganda, you will meet schoolchildren.

In the afternoon, I visit Beacon of Hope clinic, and talk with its director, Dr. Okwana, and his staff. We have high hopes this ten-bed clinic will evolve into a real hospital, and include a regional psychosocial trauma center covering northeastern Uganda and southern Sudan. Here they handle everything from infections to viruses, and undertake a lot of basic education in hygiene, pre- and post-natal care, and help families with the traumatic issues endemic to the rural poor.

In the afternoon, I visit Beacon of Hope clinic, and talk with its director, Dr. Okwana, and his staff. We have high hopes this ten-bed clinic will evolve into a real hospital, and include a regional psychosocial trauma center covering northeastern Uganda and southern Sudan. Here they handle everything from infections to viruses, and undertake a lot of basic education in hygiene, pre- and post-natal care, and help families with the traumatic issues endemic to the rural poor.

The children at Beacon of Hope gather for their assemblies and worship under the shade of a huge tree, related to the fig tree, that has become holy ground to us all. If you drive up after they have begun their worship, you can hear them singing from several hundred feet away. These kids are so full of joy and so grateful to be here, I can never think of them without feeling joyful and grateful myself.

The children at Beacon of Hope gather for their assemblies and worship under the shade of a huge tree, related to the fig tree, that has become holy ground to us all. If you drive up after they have begun their worship, you can hear them singing from several hundred feet away. These kids are so full of joy and so grateful to be here, I can never think of them without feeling joyful and grateful myself.